Make a donation to the Museum

Almost 20 Years After 9/11, “The Fathers’ Eight” Stand as a Trio

Almost 20 Years After 9/11, “The Fathers’ Eight” Stand as a Trio

The tradition of “Father’s Day” stirred to life on a Sunday in June 110 years ago in Spokane, Washington. Historically, the annual invitation to honor fatherhood was a latecomer compared to the centuries-older, spring season ritual of “Mothering Sunday.” Today, the 9/11 Memorial Museum offers a respectful salute to all fathers, and the force of fatherhood woven through our families and communities as well as history itself.

A father’s death creates a void under most any circumstance, especially so when those lives end prematurely, under sudden, violent circumstances. The atrocity of the 2001 terrorist attacks represented an inconceivable, magnified loss of fathers on a single September morning.

Contemplate, however, the anguish of fathers whose sons pre-deceased them on 9/11, rupturing the natural transition between generations and complicating parental grief. This devastation, experienced by countless fathers and father figures on September 11, was embodied in the so-called Band of Dads whose adult children vanished when the Twin Towers collapsed and spent months at Ground Zero searching for them. Mostly, but not exclusively, these men were retired New York City firefighters looking for missing sons who had followed them into the uniformed rescue services.

The media attention that came to focus on their vigil was not sought. But their determination remains deeply affecting. A series of photographs of these fathers by Curtis J. Quinn, a part of the 9/11 Memorial Museum's Collection, provide an opportunity to witness the love and fortitude motivating them, and to recognize that as their numbers shrink, ever fewer of them remain to tell this story in his own distinctive words.

The coalition described by Quinn as “the Fathers’ Eight” consisted of Bill Butler, Paul Geidel, Lee Ielpi, Jack Lynch, Dennis O’Berg, Al Petrocelli, George Reilly, and John Vigiano, Sr. The actual search group was more fluid in number, with access to Ground Zero facilitated by shared professional connections and allegiance to the FDNY, but these were not all firefighters who banded together in their suffering and search. Jack Lynch, the father of victim Michael F. Lynch (on rotation with Engine 40) was himself a retired New York City transit worker. Retired Battalion Chief Al Petrocelli’s civilian son Mark had worked in the North Tower as a commodities trader at Carr Futures. John Vigiano, Sr., a former marine and esteemed, retired FDNY captain, held the heartbreaking double distinction of looking in the rubble for two first-responder sons: the elder John, Jr., a firefighter (Ladder 132) like his father, and younger Joseph, a New York City police detective. It was heartbreak that solidified all eight men.

The much-decorated veteran of the elite FDNY special Operations Company Rescue Two, Lee Ielpi had relinquished his retirement immediately to devote long hours at the World Trade Center site digging for his son Jonathan (Squad 288) and others unaccounted for within the mountainous wreckage pile. That Tuesday morning, Jonathan had reached his father by phone, reporting that his company was en route downtown, accepting his dad’s counsel to please “stay safe.” Now a board member of the 9/11 Memorial Museum, Lee Ielpi co-founded the Tribute Center in 2006, to perpetuate the stories and memories of those ensnared by the cataclysm of September 11.

His son’s recovered turnout coat and helmet—unforgettable features of Tribute’s core exhibition—are indicative of another tragic legacy of 9/11: very few bodies were located and returned to bereaved families for proper burial. Jonathan Ielpi’s remains fell into that exceptional category. Around 126 FDNY responders have eluded any identification to the present day.

In a recent phone call, Lee Ielpi briefly referenced the fathers’ grim mission, recalling the hand shovels and small picks they deployed as they gingerly sifted through the debris, hoping to identify parts of their children. He preferred to speak about the wordless comfort and mutual support that strengthened this fraternity. Typically, the fathers met for morning coffee prior to their self-imposed shifts. They updated each other with radio reports as they navigated different sections of the site, he also recalled. And they tried to attend the memorial services and funerals of one another’s sons.

Photographer and videographer Curtis Quinn came into the orbit of the “Fathers’ Eight” through his attendance at the memorial service and subsequent funeral mass for firefighter Michael Lynch, whose remains were found six months after September 11. A native of the Bronx, Quinn shared in common with Lynch an association with the Throgs Neck neighborhood and familial ties to the firefighting profession as his father and uncle were also FDNY members.

Although his work usually focused on rock and roll and live music performances, Quinn was moved by the grief of the tight-knit Lynch family as well as the stoic dignity of its patriarch. He documented both commemorations held for Michael Lynch. He soon found a larger subject in chronicling these dedicated fathers who were toiling at Ground Zero, looking for their own sons and contributing to the recovery of other victims.

On September 3, 2002, as the nation prepared to mark the first anniversary of the attacks and the nearly three thousand lives they claimed, Quinn took his camera equipment to a studio in Chinatown. The eight fathers he had befriended had been convened there for a shoot and national press story about them. Seven were invited to wear their FDNY Class A uniforms; Jack Lynch wore a business suit and an American flag-themed tie. Each memorialized his respective son with a portrait pin. The firefighter fathers inserted depictions of their sons into the interior of their white dress hats. Quinn captured this formal but intimate reunion. Thereafter, he accompanied the same group to the pit at Ground Zero, where their bonds had been cemented over nine months of emotional labor, freely offered.

Almost 19 years later, Quinn’s photographs continue to stir emotion, with an added poignancy: time has reduced the Fathers Eight to a trio of three surviving fathers. Those left shoulder the responsibility of sharing and speaking the memories of the group’s other members.

We conclude this post with Quinn’s arresting photograph of Battalion Chief Al Petrocelli. On his dress coat one can see the picture pin of his beloved son, Mark, who is also glimpsed inside the uniform cap, a companion to his father’s everyday thoughts. On April 1 of this exceptionally discomforting and tragic year faced by the world, the 73-year-old Staten Island husband, father, grandfather, and distinguished civil servant died. He did not pass away from the infirmities of aging or from complications tied to his exposure to the pernicious conditions at Ground Zero. Rather, he fell victim to the novel coronavirus, to which all too many 9/11 recovery workers and volunteers are particularly susceptible.

May all these lost fathers, and casualties of COVID-19, rest in peace and stay eternal in the hearts and minds of their loved ones, coworkers, and neighbors.

By Jan Seidler Ramirez, Executive Vice President of Collections & Chief Curator, 9/11 Memorial & Museum

Previous Post

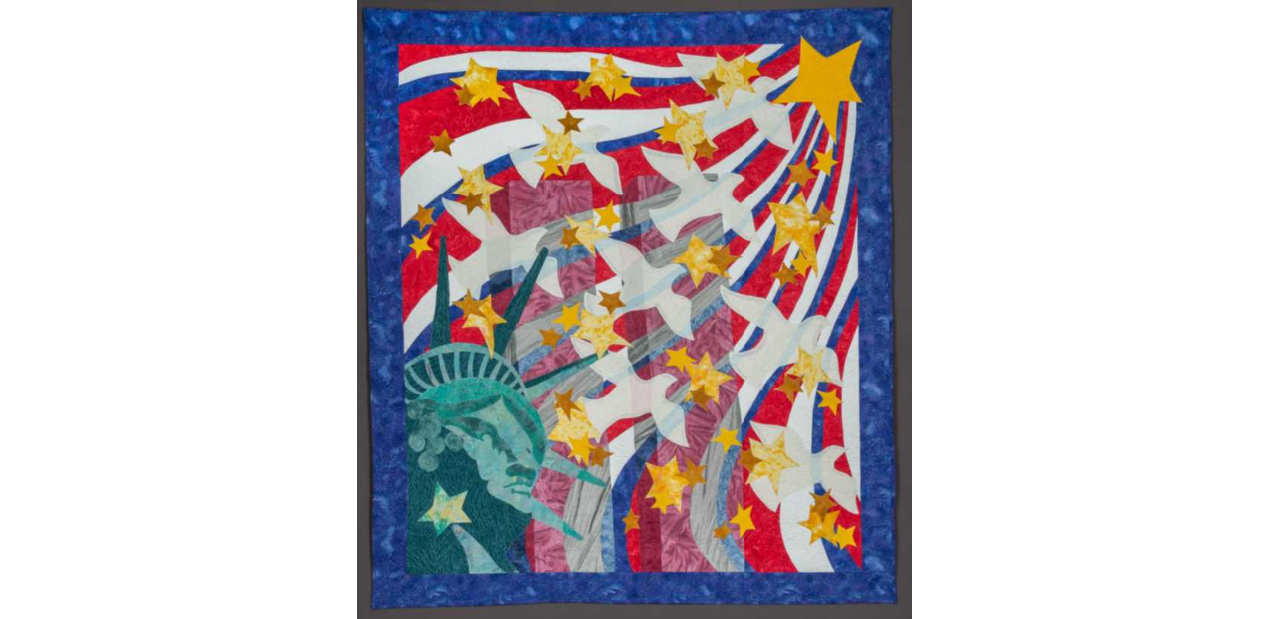

Quilting After 9/11

Overwhelmed by grief, fear, and anger in the wake of 9/11, people around the world searched for ways to help. For those unable to participate in the rescue and recovery efforts at the attack sites, quilt making became an option for offering practical, creative, and symbolic consolation to, and support for those who were directly affected by the attacks.

Next Post

Museum Partners with USO and Tunnel to Towers to Deliver Masks to Frontline Responders

The 9/11 Memorial & Museum partnered with the USO of Metropolitan New York and the Stephen Siller Tunnels to Towers Foundation earlier this month to deliver more than 1,000 masks to frontline responders across the city.