Make a donation to the Museum

Faces of the First Helpers: Portraits by Holger Keifel

Faces of the First Helpers: Portraits by Holger Keifel

- Published May 27, 2020

Published May 27, 2020

As we look forward to commemorating the 18th anniversary of the formal end of recovery operations at Ground Zero, our thoughts are with the brave men and women combating the COVID-19 pandemic health crisis today. Jan Seidler Ramirez, executive vice president of collections and chief curator at the 9/11 Memorial & Museum, reflects on the power of these photographic portraits of those who answered the call in 2001 as we salute a new generation of heroes today.

Eighteen years ago, before learning his name or that his pictures were from a larger family of faces, I saw two photographs by Holger Keifel clipped to a hanging line inside a SoHo storefront. The space, on Prince Street, had been converted to a gallery for the open invitation, ever-evolving exhibition, “Here is New York: A Democracy of Photographs.” Many of the submissions to that memorable project testified to the magnitude of devastation at Ground Zero. Some mirrored the shock of public witness; others, the realization of human suffering and loss resulting from the terror attacks. This pair of portraits had a different focus, however. Their subjects gazed at the camera, face forward. Although nameless, they looked familiar as most any New Yorker encountered every day on the subways, sidewalks, and other civic crossing spaces. They seemed fatigued but not despairing. Their down-to-earth dignity left a strong impression.

Matilda Guiracocha, Asbestos worker

Some years later, after transitioning to the role of chief curator at the 9/11 Memorial Museum, I met their German-born, Long Island City–based creator. Known for his portraits of boxers, photographer Holger Keifel shared the framing context of these vividly remembered faces. Recorded through a combination of chance and strategic objective, they were part of a series of 24 images of rescue workers he managed to capture 48 hours after the World Trade Center’s destruction. His contact with each had been fleeting—just long enough to jot down individual names and occupations.

Arthur McLoughlin, Firefighter

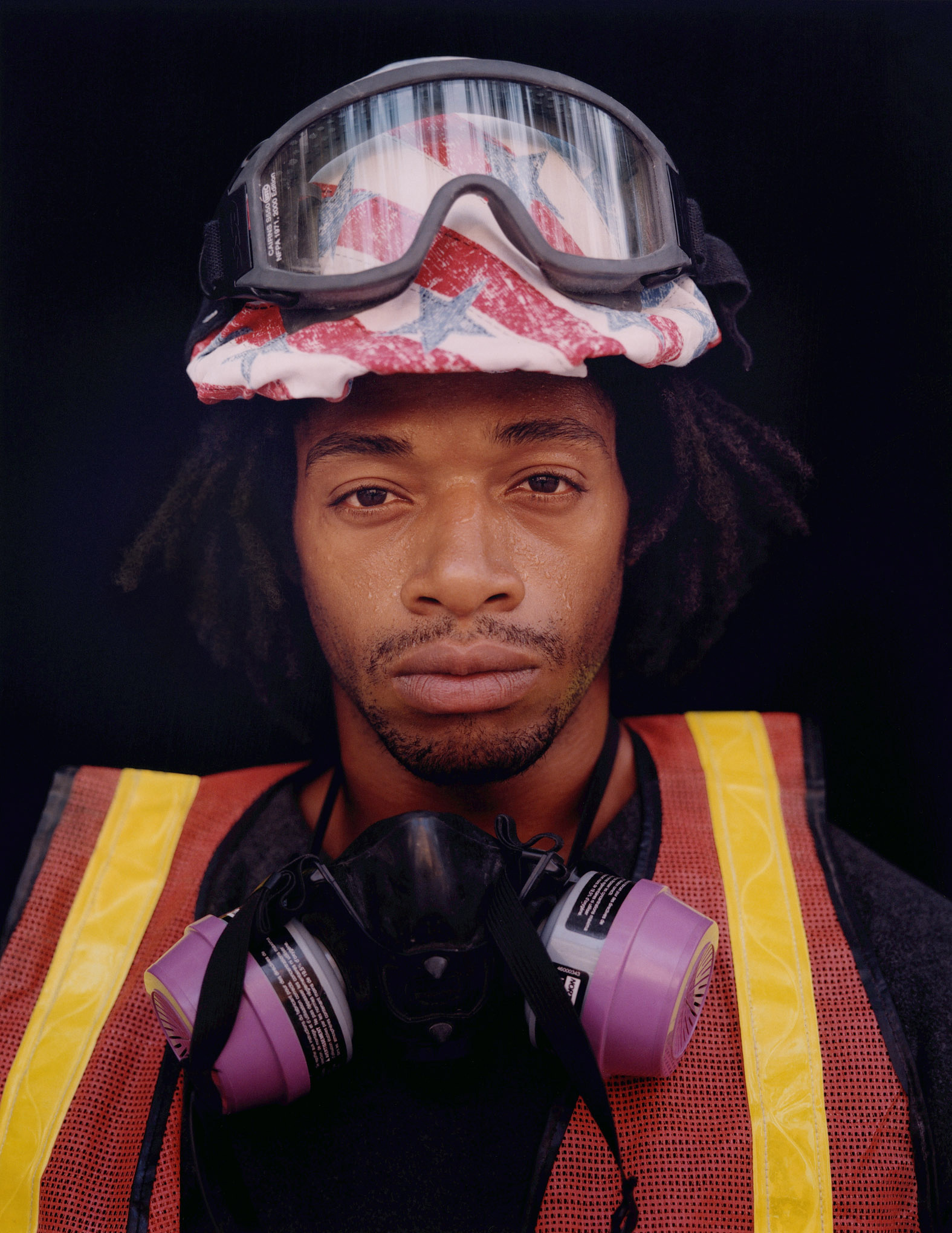

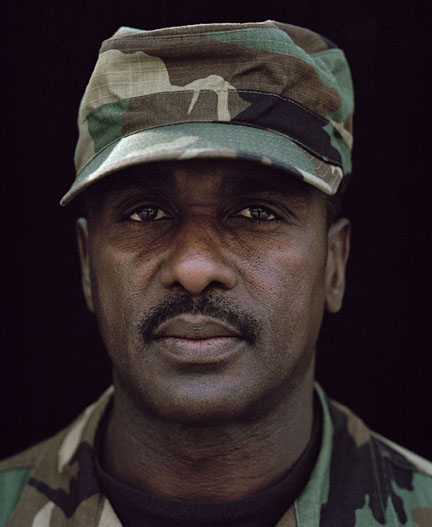

The list vouches for the diversity that has always been a hallmark of the city’s populace: surnames range from Alimohammadi, Brown, Guiracocha, and Levine, to McLoughlin, Placheriski, Rodriguez, and Spivak. The roster of connected jobs belonged to both trained responders and fiercely determined volunteers. Those cited by these frontline helpers and would-be healers include firefighter, policeman, trauma physician, and military as well as asbestos worker, architect, reverend, and volunteer (the most common self-identifier).

Jean Spivak, Volunteer

Keifel also summarized his own on backstory in connection with these photographs. On the morning of September 11, he was retrieving some film at his lab in SoHo when hijacked Flight 11 struck the North Tower. Delayed in his awareness that a terrorist attack was unfolding downtown, Keifel sensed public tension rising. He decided to hustle home to retrieve his camera but became stranded in Queens when train service was halted. Once the cause and gravity of the events were known, he felt compelled to do something to chronicle the reverberations of this unprecedented tragedy.

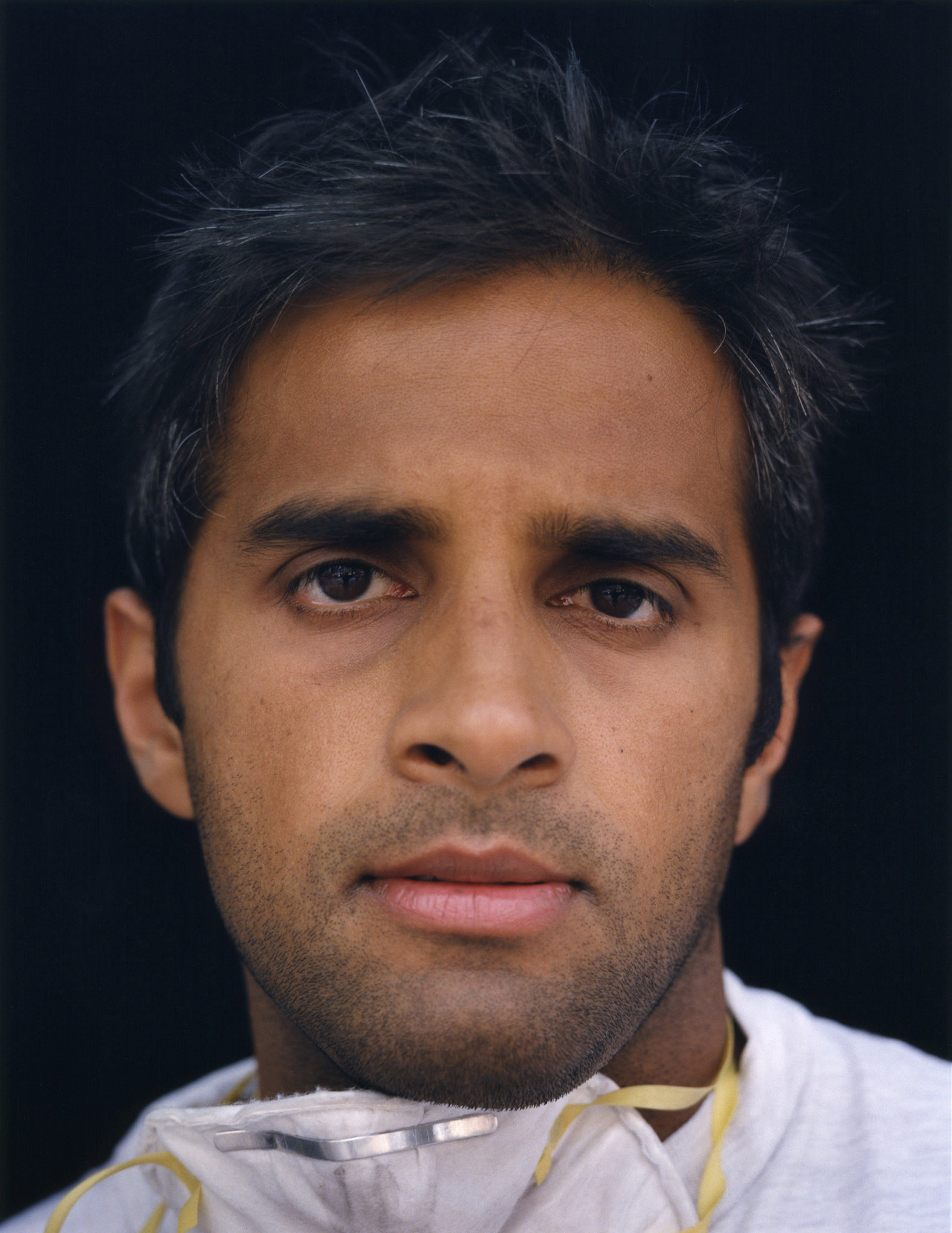

Maulik Trivedi, Trauma Physician

On September 13, he headed into Manhattan, packing his tripod and camera—a Mamiya RZ single lens reflex camera—along with some black velvet adaptable for an impromptu studio backdrop. Using his journalist-issued ‘police ID card’ to clear or circumvent checkpoints along the way, Keifel got as far south into the new Frozen Zone as Washington Market Place, a small community park in TriBeCa. There, he jury-rigged a plein-air studio by clamping his velvet drapery to a fence and steadying his camera on the portable tripod. His objective was to capture portraits of emergency workers as they finished their grueling shifts at Ground Zero and were northbound, seeking rest.

Tamru, Volunteer

The resulting two dozen photographs convey an engaging immediacy and intimacy. They also serve as a barometer sampling of the enormity of the rescue and recovery operations, as measured in the faces of those on the frontlines: bloodshot eyes, sweat beaded on brows, dust coating helmets and clothing, but above all, conveying unspoken determination. In 2002, Keifel’s portraits brought a sense of that inspiring resolve to an audience far removed from Ground Zero when gathered as a solo exhibition at the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio. Eight from the group were acquired by the 9/11 Memorial Museum in 2012, having earlier displayed a subset if these unshakable faces to welcome those exiting the newly dedicated 9/11 Memorial through our temporary visitor center at 90 West Street.

Lonnie Brown, National Guard

We share them now to acknowledge the selflessness of those who rushed to help in the aftermath of 9/11, and the comparable heroism of those in the essential service trenches today, combatting the COVID-19 pandemic health crisis.

By Jan Seidler Ramirez, Executive Vice President of Collections & Chief Curator, 9/11 Memorial & Museum

Previous Post

9/11 Memorial Commemorates Memorial Day

The Lens: Capturing Life and Events at the 9/11 Memorial & Museum is a photography series devoted to documenting moments big and small that unfold at the 9/11 Memorial and Museum.

Next Post

Upcoming Public Program to Discuss FDNY’s Response to First Responders’ Health

The second program in our new digital conversation series will be “Rescue and Recovery,” with Dr. Kerry Kelly, former chief medical officer for the FDNY (1994–2018), on Friday, May 29, at 2 p.m. (ET).