Make a donation to the Museum

"The Hardest Job Was Leaving:" Museum Volunteer Reflects on the Rescue and Recovery Effort

"The Hardest Job Was Leaving:" Museum Volunteer Reflects on the Rescue and Recovery Effort

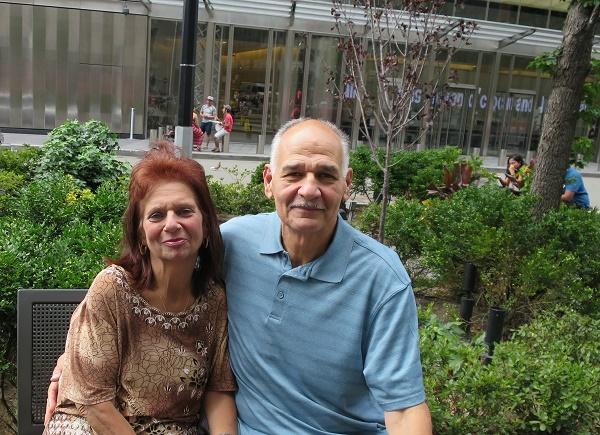

On the morning of September 11, Anthony Palmeri and his partner at the Department of Sanitation, Joe Smith, were working their assigned route in upper Manhattan when a passerby came up to them and breathlessly shared the news of the attack. At the time, Palmeri assumed it was a small plane that had flown into the tower.

“I didn’t take it as seriously as I should have,” Palmeri says, thinking back to that morning. “I regret doing that.”

Seventeen minutes later, Palmeri and Joe got a sobering update: a second plane had crashed into the South Tower.

“Joe looked at me and said, ‘Anthony – terrorists.’ I’ll never forget that.”

The two partners were ordered back to the DSNY garage on 215th Street. The garage sits on the East River, and from there they had a clear view of lower Manhattan, where they could see smoke rising over the skyline.

Palmeri and his coworkers watched on television as the enormity of the day hit. They were eventually sent home; their sanitation duties, like much of the city, had come to a halt.

He remembers an unnerving stillness as he made his way to work the next day. The roads were nearly empty except for National Guard members, state troopers and police.

“Have you ever been on a highway late at night when you’re the only car on the road? That’s what it was like for me that morning,” he says. “The mood was dark.”

Palmeri went to work but began to wonder how he could help the efforts at Ground Zero, where thousands of rescue and recovery workers were now sifting through the smoky rubble.

Palmeri was then a volunteer firefighter for Fire Company Engine 612 in Lodi, N.J. He joined the department around 1979 after witnessing his wife’s grandmother die of a heart attack and having felt helpless to save her life.

Members of the fire department were on standby in the days after September 11, and even though it became clear that the company wasn’t going to Ground Zero, Palmeri was determined to make it down there somehow.

DSNY asked workers if they wanted to volunteer. Palmeri signed up.

“I was conflicted,” he remembers. “I felt like if I just go rush down there to do something, am I just grandstanding in a way? I struggle with stuff like that, because it’s not about me or what I do. I just really wanted to help.”

About a week after the attacks, Palmeri began his work at Ground Zero, “never expecting to spend that much time there.” He ended up staying through to the removal of the Last Column on May 30, 2002, the recognized end of the rescue and recovery period.

“Our job was to do everything and anything that we had to do to clean up the area,” he says.

He and the other volunteers started at the perimeter of Ground Zero, clearing debris and refuse from streets and businesses.

“Everything was closed at the time, so you had a lot of rotting food and waste and so forth,” he says.

Reminders of the death and destruction that had occurred just days earlier were everywhere.

“My partner and I would take a fire hose and we would have to wash off many of the buildings and the streets of the thick layers of ash that were formed,” Palmeri says. His focus was on supporting the firefighters and recovery workers as they cleared the site.

“My heart was with the firefighters, what they had to do,” Palmeri says. “If they were to say to me, ‘Hey, Anthony, you think you could do this here?’ my partner and I listened.”

He says his work involved clearing “a little bit of everything and anything that was in front of us to help get the city back to normal.”

Among his duties was helping to remove waste from all the food that was being served to workers. Companies like McDonald’s came from all over to feed them. Palmeri estimates that about 15,000 meals were served every day.

DSNY volunteers also helped tear down the temporary shacks that workers used to store tools and other equipment used in the relief and recovery effort. Palmeri also made visits to a temporary morgue at the site and supported and consoled family members paying their respects beside the refrigerated trailers that contained remains of the victims.

He says it was an overwhelming job, both physically and emotionally.

“I think the hardest part for me was, you know, as you’re cleaning up and you see these strangers walking around like zombies, holding signs up: ‘Anybody seen my brother, my sister, my wife, my children?’

“When you looked at them and then turned your eyes towards the pile, all sorts of emotions run through your head,” he says. “I think for me that gave me a little bit of inner strength to do whatever I could, maybe for that person to get the answer that they were looking for.”

For Palmeri, the catastrophe also led to moments of clarity and beauty.

“It was an absolutely wonderful, humbling feeling to be connected with such a tragedy – that everyone was on the same page,” he says. “I just don’t think there’s another feeling that a person can have in their life that I had during that time.”

The official recovery mission at Ground Zero ended in May 2002. Palmeri says the most difficult thing for him and many others was wrapping up.

“I think the hardest job was leaving. Nobody I know of wanted to leave. We were there for nine months. That was our home,” he says. “A lot of us felt like we weren’t finished. We still need to be here. We wanted to be there.”

One of the biggest honors of Palmeri’s life was being invited to take part in the Last Column ceremony on May 30, 2002, when the final steel beam was removed from the site.

“That morning when I stepped foot on the ramp, it was just an incredible, humbling feeling,” he remembers. “I’m thinking, ‘How lucky am I?’ I’m not these police officers that went in there. I’m not these firefighters that went in there. I’m not a family member. But look where I’m standing.

“I just wish I could have grabbed everybody that I know, everybody that means anything in my life – my family, my friends – and have them feel what I was feeling at that moment. It was just an incredible, incredible honor to be with them.

“At the time I don’t know if I realized how important, how wonderful it actually was and how it was going to affect me for the rest of my life.”

But Palmeri’s work at Ground Zero wasn’t over. In 2006, a woman he’d met through his work at the site encouraged him to volunteer at the 9/11 Tribute Center, a place where victims’ family members and others with personal ties to the tragedy shared their experiences with the public.

“I said at the time, ‘I’m a sanitation worker. What am I going to tell people?’” he says. “Thank goodness I was wrong. It gave me a way of not leaving Ground Zero.”

Palmeri retired from DSNY in 2007. He started volunteering at the Tribute Center and giving tours of the site. Rather than talk about his work at Ground Zero, he wanted to share with visitors the stories of strength and goodness he’d witnessed from rescue workers, survivors and family members.

“I want people who weren’t here, who only saw on television, to know them,” he says. “They’re going to come. They’re going to see this here and they’re going to take, hopefully, not always a sad story but a good story back.”

In May 2014, Palmeri and other volunteers were invited into the 9/11 Memorial & Museum, which was still under construction at the time. Palmeri remembers walking into the darkened and still-unfinished Museum, where he came face to face with the Last Column. It was no longer towering over the rubble of the World Trade Center but standing as a centerpiece in a Museum that would soon be welcoming visitors from around the world.

“I can’t describe the feeling that I had. I think every image, every person I talked to, everything that was in my head at the time that I was down there, just came flashing back,” he says. “After so many years not seeing those things, they became all too real.”

The hardest part for Palmeri was the historical exhibition, which tells the story of 9/11 through artifacts, images, first-person testimony, and archival audio and video recordings. He says it took him several visits before he could begin to take it in.

“I don’t think I even finished it,” he says. “I still have a hard time going in there.”

At 68, he now lives in Maryland, where he’s grateful for the time he gets to spend with his family, including his daughter and grandchildren. But it’s hard being away from a place that holds so much meaning for him – where he witnessed the worst and best of humanity.

“I cannot get to the Museum, to Ground Zero, to the Tribute Center nearly as much as I used to when I lived right across the river in New Jersey. That’s a very, very difficult thing for me.”

On May 30, Palmeri will attend the dedication of the 9/11 Memorial Glade, which will honor the ongoing sacrifice of rescue, recovery, and relief workers, and the survivors and members of the lower Manhattan community, who are sick or have died from exposure to toxins in the aftermath of 9/11.

“I think it’s wonderful,” he says of the Glade. “I’m hoping the visitors that come will feel the human bond that was formed by everybody that was there.”

It’s been 17 years since thousands of strangers put their hands and hearts into returning lower Manhattan to a city shaken at its core. Palmeri says that history lives on, that 9/11 is “not a day to remember” but “a day to never forget.”

“It’s a never-ending book called September 11, and with the Glade being there, it’s just another chapter and another story that’s going to be told.”

By Adam Warner

Previous Post

Tonight at the 9/11 Memorial Museum: Filmmaker and Activist Deeyah Khan Discusses Extremism

On Thursday, May 16, the 9/11 Memorial & Museum will host a public program featuring Emmy Award–winning documentary filmmaker and activist Deeyah Khan, who will discuss her filmmaking and her quest to understand what draws people to extremist ideologies.

Next Post

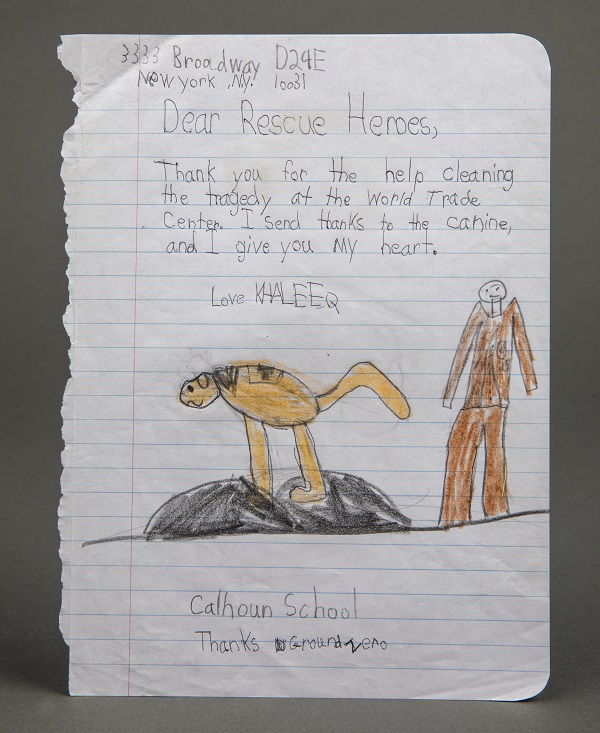

Artifacts Tell the Story of 9/11 Rescue and Recovery Dogs and Their Handlers

Dogs played an important role in 9/11 rescue and recovery efforts. The 9/11 Memorial Museum’s collection contains a number of artifacts that tell the story of these heroic canines.