Make a donation to the Museum

Food for the Soul: The Restaurants of Ground Zero

Food for the Soul: The Restaurants of Ground Zero

On September 13, 2001, Antonio “Nino” Vendome opened his family’s New York City restaurant, Nino’s, to a new clientele.

Before the 9/11 attacks, the Italian eatery on Canal Street served a couple hundred lunches and dinners a day to Manhattan diners. Only 48 hours after the attacks, however, Nino’s had a different mission. The restaurant, located a mile from Ground Zero, transformed into an around-the-clock operation, providing weary rescue and recovery workers with thousands of hot meals every day.

Over the course of the next nine months, Nino Vendome, his family, and an army of volunteers would serve more than 500,000 meals to the police officers, firefighters, military personnel, sanitation workers, ironworkers, laborers, and countless others working at Ground Zero. Children’s drawings and thank-you cards papered the walls of the restaurant, offering gratitude and encouragement. Volunteers included local residents and victims’ friends and family members, along with beauty pageant queens, professional athletes, and famous actors.

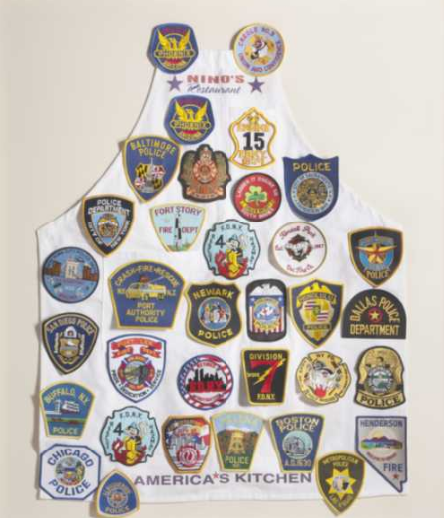

As a token of gratitude to the Nino’s staff and volunteers, law enforcement officers, firefighters, and workers left behind patches and pins with their department or union logos. Nino Vendome’s mother, Giuseppa, attached the patches to chefs’ aprons, which she later displayed behind the bar counter.

Nino’s wasn’t the only restaurant to offer hospitality to the Ground Zero workforce. Across the city, chefs, charitable organizations, and volunteers with a zest for cooking answered the call to help their fellow New Yorkers, joining together as a community to share food for both body and soul.

Albert Capsouto—owner of the Tribeca restaurant Capsouto Frères—served free lunches and dinners and weekend brunches during the recovery period, with their famous eggs Benedict a particular favorite. “We decided to make our restaurant an anchor of the neighborhood,” Capsouto said. “And we served food to whoever was there—either rescue workers, utility people, firemen, policemen. Anybody with a uniform, anybody without a uniform. Neighbors.”

Ruth Reichl, chef and editor in chief of Gourmet, called on staff to join her at the magazine’s test kitchens in Times Square in the days after the 9/11 attacks. Reichl arrived to find the kitchens full of colleagues with their friends and families, bearing groceries and ready to help. They cooked chili, cornbread, lasagna, and brownies, packed the food into coolers, and delivered it straight to the World Trade Center site. “We were attempting to snatch hope from the rubble of our broken city,” Reichl would write years later, “and food was the perfect way to do it.”

Other improvised restaurants sprung up in unlikely places. In an abandoned storefront on Liberty Street, award-winning restauranteur David Bouley worked with the American Red Cross to create the Green Tarp Café, named for the green tarpaulin draped over its broken windows. Workers could also find respite at a massive Salvation Army tent, nicknamed the Taj Mahal, or grab coffee and soup at a makeshift wooden hut inside Ground Zero that they called the Hard Hat Café.

As Albert Capsouto would later note, the “social nourishment” that these restaurants and pop-up cafeterias offered was often just as important as “feeding an appetite.” Providing fellowship, conversation, and a place to relax—as well as hot meals—the chefs, restaurant owners, and thousands of volunteers who served the Ground Zero workforce did more than fill bellies. They lifted spirits.

By Isabela Morales, Manager of Exhibition Development, 9/11 Memorial & Museum

Previous Post

Former NGA Director Describes Role of Intelligence Community in Hunt for Bin Laden

During the program, Cardillo described his time in the Obama administration in the weeks leading to Operation Neptune Spear. He offered several observations about leadership and collaboration in the government that were shaped by the team’s experience of 9/11.

Next Post

K-9 Courage Honors the Comfort and Companionship Provided by Canine Responders

Search and rescue dogs went beyond their specialized training to elevate the spirits of responders at Ground Zero. Recovery workers approached and embraced the search dogs, which were brightening the dark days on the pile. Workers seeking a break hugged, petted, gave treats to, and played with the dogs.