Make a donation to the Museum

Remembering the Women of Ground Zero

Remembering the Women of Ground Zero

On 9/11 and in the weeks and months following the attacks, tens of thousands of firefighters, police officers, construction workers, search-and-rescue dogs, volunteers, and many others converged at the World Trade Center site to aid in search and rescue and ultimately recovery efforts at Ground Zero.

Women made significant contributions to every aspect of these efforts—from Kathy N. Mazza, Yamel Josefina Merino, and Moira Ann Smith, who gave their lives to save others, to those who served around the site in morgues and family assistance centers.

Among this diverse league of dedicated women involved in the rescue and recovery efforts, today we share but four, whose stories and experiences have been captured in the 9/11 Memorial Museum’s collection.

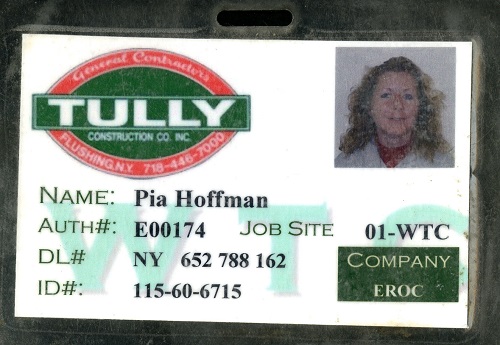

Tully Construction identification card issued to Pia Hofmann. Gift of Pia Hofmann.

Pia Hofmann

Born in Germany, Pia Hofmann came to New York where she “started out as a dress designer and ended up astride a 100-ton crane” as an operating engineer with Local 14. In September 2001, Hofmann had just received her crane-operating license, and when she arrived at Ground Zero a week after the attacks, she was assigned to her own rig.

“Everything suddenly made sense,” Hofmann told the Chicago Tribune in 2002. “Being down there was the first time in my life I was sure I was in the right place at the right time.”

During her eight months at Ground Zero, Hofmann worked demanding hours for several different companies, and at one point she only narrowly escaped a falling steel beam. Hofmann left a lasting impression on the people with whom she worked, and she had a reputation for speaking her mind. She is also remembered as “virtually the only woman operating a big rig at the site and had been just one of 12 people chosen to carry out the final, flag-draped stretcher during the nationally televised closing ceremony,” according to the Chicago Tribune.

Three of Hofmann’s badges and identification cards were donated to the Museum’s collection and are currently on display in the historical exhibition.

Brenda Berkman

Brenda Berkman was enrolled in her third year of law school when the New York City Fire Department announced that women could take the exam to become firefighters in 1978. After passing the written portion of the exam, Berkman and 89 other women subsequently failed the physical portion. It was stated by an official that their physical test was “the most difficult the department had ever administered, [and] was designed more to keep women out than to accurately assess job-related skills.” After Berkman’s requests for a fairer test were ignored, she filed an ultimately successful class-action lawsuit: Brenda Berkman, et al. v. The City of New York, which allowed for her and 40 other women to enter the fire academy in 1982. By the time she retired in 2006, she had become one of the highest-ranking women in the FDNY over her 25-year career.

On September 11, Berkman operated as a fire officer, remaining at Ground Zero until the end of rescue and recovery efforts in May 2002. Berkman went on to tell CNN in 2011 that “September 11 made us all feel like we could never trust a sunny day again.”

Berkman has donated a multitude of objects to the 9/11 Memorial Museum collection, including her original artwork.

Sonia Agron

Sonia Agron waited until the morning of September 12, 2001, to find out if her husband, NYPD officer Jose Agron, was alive. After finding out that he had in fact survived, Agron felt compelled to put her EMS training into action.

“The last message we got from him around 4 p.m. that day was that he was heading to 7 World Trade Center, which fell a short time later,” said Agron. “We waited until 10, 11 p.m. and at that point, [we] had family all around us. We started to plan for the funeral, having seen that video of 7 WTC coming down over and over on the news.”

A lifelong resident of Bronx, Agron volunteered as a recovery worker on overnight shifts with the American Red Cross for weeks at Ground Zero after 9/11. “After 9/11, for those few weeks I had lost my trust in the world. I couldn’t look at anyone on the train. It was paranoia. But coming down here, it restored my faith in humanity,” Agron said.

Sonia now volunteers as a Museum docent as has shared her story as part of the 9/11 Memorial & Museum’s Anniversary in the Schools webinar.

Black leather women's boots worn by Carol Orazem on Sept. 11, 2001. Gift of Carol Orazem.

Carol Orazem

Carol Orazem joined the New York Police Department in 1983 at a time when the department was predominately male. After working for seven years at Manhattan’s First Precinct, Orazem eventually moved to the NYPD intelligence division in Brooklyn. On the evening of September 10, Orazem was working undercover for a sting operation until the early morning hours of September 11. As a result, she was asleep when Flight 11 struck the World Trade Center’s North Tower at 8:46 a.m.

She was soon dispatched to Liberty and West Streets clad in her raid jacket and a pair of boots. Orazem remained at Ground Zero throughout September 11 and into the morning of September 12. After returning home, Orazem discarded her clothes from that day but kept her boots—the soles of which bear melted scars from the extreme heat conditions on-site. Orazem retired from the NYPD in 2002.

Orazem donated her boots to the 9/11 Memorial Museum collection in 2014 when she told the Associated Press, “Now, at the museum, ‘I know that they're taken care of.’”

By 9/11 Memorial Staff

Previous Post

Museum Offers New Virtual Tour of “Revealed” Exhibition

The 9/11 Memorial & Museum has just launched its newest virtual tour offering, which provides an exclusive look at the special exhibition, Revealed: The Hunt for Bin Laden.

Next Post

The Bamiyan Buddhas and the Role of Cultural Heritage in Afghanistan Peace-Building

Last week, the 9/11 Memorial & Museum welcomed Dr. Morwari Zafar, an anthropologist with experience in international development and national security, and currently an adjunct lecturer at Georgetown University’s Security Studies program, to discuss the role cultural heritage plays in Afghanistan’s nation-building up to and following the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas 20 years ago.